NYC’s new mayor identifies as democratic socialist; critics challenge his bodega store proposal as economically unfeasible

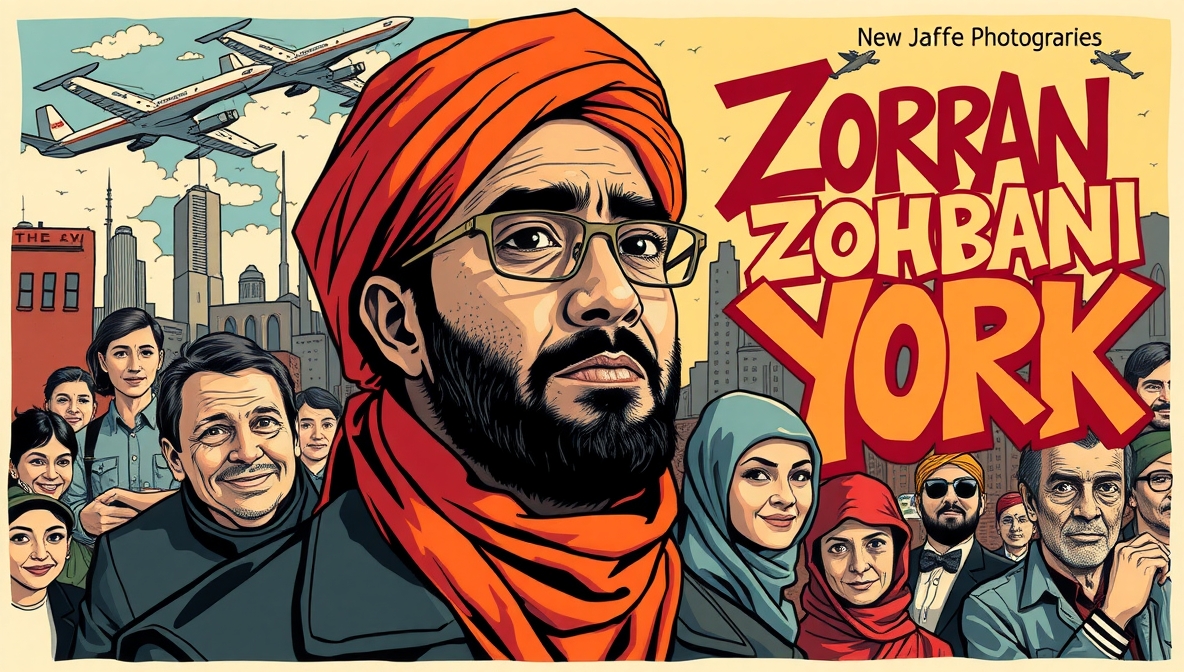

New York City Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani identifies as a democratic socialist and belongs to the Democratic Socialists of America, a distinction that carries significant implications for how he will govern the nation’s largest city. Understanding democratic socialism in the Mamdani context requires examining both its ideological foundations and its practical policy implications, particularly regarding controversial proposals like city-owned grocery stores that critics argue are economically unsustainable. Democratic socialism as a political movement emphasizes democratic governance of the economy with a focus on reducing inequality, providing universal public services, and shifting power from corporations toward workers and communities. Mamdani’s platform reflects these themes with proposals for city-owned groceries, free public transportation, universal childcare, and aggressive rent controls on stabilized housing units. The ideology draws from American political traditions including Eugene Debs, the Socialist Party leader whom Mamdani quoted in his victory speech, and contemporary figures like Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. According to NPR’s analysis of democratic socialism, the ideology aims to preserve democratic processes while fundamentally restructuring economic relationships. For Mamdani, this means accepting market mechanisms where they function well while creating public alternatives where private markets fail to serve low-income communities. The bodega store proposal encapsulates both democratic socialism’s idealistic promise and its economic vulnerabilities. Mamdani campaigned on plans for the city to own and operate grocery stores in food deserts, areas of the city where affordable fresh produce is inaccessible and residents depend on bodegas and fast-food establishments. His pitch framed city-owned groceries as an equity measure ensuring that working families could access nutritious food. As reported by the Times of Israel and other outlets analyzing Mamdani’s economic platform, critics argue the proposal contains fundamental flaws. Economists and policy analysts note that the supermarket business operates on thin profit margins, typically 1-3 percent of sales. Even unionized supermarkets struggle against big-box competitors and rising real estate costs. A city-owned supermarket would face identical cost pressures while lacking the efficiency of large chain operations or the flexibility to adapt quickly to market changes. The Times of Israel’s Ori Solow analysis of Mamdani’s economic platform noted that city ownership does not eliminate the structural challenges facing retail food establishments. Without profitability, the city would face perpetual subsidy requirements. The business model for city-owned groceries in other cities has consistently demonstrated this problem. Democratically operated or city-owned supermarkets in cities ranging from Philadelphia to Oakland have required substantial ongoing subsidies and eventually struggled to remain operational. The proposal reflects a broader tension in democratic socialism between recognizing genuine market failures and assuming that public ownership automatically solves underlying economic problems. Food deserts exist because profit margins are too low to sustain conventional supermarket operations in low-income neighborhoods. Public ownership does not change the underlying economics that created the desert in the first place. Yet Mamdani supporters argue that even subsidized city-owned groceries would serve essential equity functions, ensuring access to nutrition as a public good rather than a market commodity. From this perspective, the fact that city grocery operations require subsidy is not a failure but a recognition that some essential services should not be profit-dependent. Schools require substantial public subsidy. Public hospitals operate at losses. Public transportation requires continuous public funding. Democratic socialists argue that food access belongs in this category of essential public services. On the political economy level, the bodega proposal also reflects Mamdani’s challenge to traditional small business interests. New York’s bodega community has organized politically and sometimes positioned itself against large-scale municipal initiatives. Mamdani’s platform implicitly argues that bodegas, while serving important neighborhood functions, cannot substitute for full-service supermarkets offering diverse fresh produce. Bodega owners’ profit margins depend partly on limiting competition from larger retail operations, creating an interest alignment between bodegas and large grocery chains that both benefit from food desert conditions. This analysis, emerging from democratic socialist political economy, views small business not as an inherently progressive force but as part of the capitalist system that constrains equity. However, the bodega counter-argument remains powerful. Small bodegas employ neighborhood residents and are often owned by immigrant families. Mamdani’s proposal to create municipal competition with these businesses, even in the name of equity, requires politically difficult decisions about accepting displacement of existing small business owners. Some democratic socialists prioritize protecting small business as a site of community wealth accumulation, particularly for communities of color. Others view this as romantic nostalgia for a capitalism that cannot deliver equity outcomes. This tension pervades democratic socialist policy analysis. The tension between Mamdani’s democratic socialist ideology and governing reality emerged throughout his transition team announcements. Mamdani’s appointments included both ideological allies like Alex Vitale, author of The End of Policing and a consistent abolitionist voice, and pragmatists like Dean Fuleihan, an experienced city administrator with conventional management credentials. Vitale and others on the transition team push Mamdani toward fulfilling DSA’s radical vision. Fuleihan and career administrators counsel feasibility and incremental implementation. The bodega proposal will likely fall somewhere between these poles. Mamdani may pursue some form of city procurement preference for fresh produce in low-income communities without establishing fully city-owned supermarket operations. He might partner with nonprofit grocery operators or provide subsidy to private groceries that meet affordability standards. These compromise approaches satisfy neither pure democratic socialists nor market economists, yet represent how democratic socialism actually functions in governance. Mamdani’s economic platform challenges traditional neoliberal assumptions that markets should allocate essential services. His bodega proposal, whatever its economic flaws, attempts to center equity and community control rather than profit as organizing principles. Whether implementation proves effective matters less politically than whether Mamdani demonstrates genuine effort to prioritize working-class economic interests over established interests that benefited from previous administrations.