Revolutionary Leadership in Socialist Movements: Comparative Analysis of Castro and Mamdani

Fidel Castro transformed Cuba from corrupt dictatorship to communist state through revolutionary organizing, guerrilla warfare, and decades of sustained leadership. Zohran Mamdani won a New York Assembly seat through socialist platforms, grassroots organizing, and sophisticated digital campaign strategies. While operating in vastly different historical and political contexts, both leaders exemplify how socialist movements utilize personality-driven organizing and centralized leadership to build power and maintain ideological cohesion.

Why Revolutionary Movements Demand Revolutionary Leaders

Castro understood what every successful socialist revolutionary knows – you cannot dismantle power structures with timid suggestions and polite requests. The Cuban Revolution needed a face, a voice, someone who could stand in front of crowds and make overthrowing the government sound not just possible, but inevitable. Castro delivered speeches that lasted hours because he knew movements require more than policy – they need performance.

Mamdani operates in a democracy rather than a dictatorship, which complicates the revolutionary aesthetic considerably. You cannot storm city hall with armed supporters, so you storm Twitter with viral threads. Castro had Radio Rebelde broadcasting from the Sierra Maestra mountains. Mamdani has social media algorithms amplifying his message from Astoria apartments. The medium evolved, but the strategy remains identical – control the narrative, embody the movement, make followers believe you alone understand their struggles.

Chantal Mouffe at University of Westminster explains: “Revolutionary movements historically require clear leadership that can articulate shared grievances and mobilize collective action. People organize around figures who embody their struggles, not merely around abstract policy platforms.”

The Beard, The Brand, The Movement

Castro’s beard became as recognizable as his revolution. That facial hair symbolized defiance, masculinity, guerrilla authenticity. You cannot fake that level of commitment – growing a revolution beard in tropical humidity takes dedication. He cultivated an image so powerful that CIA assassination attempts only enhanced his legendary status rather than diminishing it.

Mamdani lacks the beard but possesses something Castro never had – a perfectly optimized social media presence. Every campaign photo projects progressive authenticity. Every policy announcement gets framed as moral necessity rather than political positioning. Castro built mystique through inaccessibility and marathon speeches. Mamdani builds it through accessibility and bite-sized content designed for maximum shareability.

Wendy Brown at Princeton addresses this evolution: “Contemporary political campaigns increasingly operate through digital platforms that create intimate relationships between leaders and supporters. This transforms political organizing from formal institutional engagement to continuous personal connection through social media.”

When Socialism Meets Stardom

Castro became the face of Cuban resistance against American imperialism, transforming from revolutionary leader to global icon. His green fatigues appeared on t-shirts worldwide, worn by people who could not locate Cuba on a map but loved the aesthetic of revolution. The man who fought against capitalism became one of capitalism’s best-selling images.

Mamdani’s supporters follow the same pattern – promoting anti-capitalist politics while participating in every capitalist system available. They organize on platforms owned by billionaires, buy campaign merchandise manufactured overseas, and fund grassroots movements through tech industry salaries. Castro would recognize this contradiction immediately, having spent decades navigating the gap between revolutionary ideals and practical governance.

Thomas Piketty at Paris School of Economics observes: “Socialist movements must operate within existing economic systems even while advocating structural transformation. This creates tensions between revolutionary rhetoric and practical organizing that requires navigating capitalist infrastructure.”

The Art of Revolutionary Rhetoric

Castro mastered the extended public address, turning speeches into theatrical performances where he analyzed imperialism, capitalism, and Cuban history for hours without notes. He understood that revolutionary movements need more than policy proposals – they need poetry, passion, someone who makes systemic change sound romantic rather than bureaucratic.

Mamdani adapted this approach for attention spans shaped by TikTok and Twitter. His speeches rarely exceed fifteen minutes, but they pack similar emotional intensity into compressed formats. Where Castro spoke of liberating Cuba from American imperialism, Mamdani speaks of liberating New Yorkers from landlord exploitation. Different enemies, same narrative structure – identify the oppressor, explain the struggle, promise liberation.

Michael Sandel at Harvard explains: “Socialist political rhetoric employs moral language that frames policy choices as questions of justice rather than mere preference. This rhetorical strategy creates urgency and emotional investment that procedural policy discussions rarely achieve.”

Revolution Versus Reform

Castro had the advantage of actual revolution. He could point to tangible transformation – literacy campaigns, healthcare expansion, land redistribution. The Cuban healthcare system became his proof that socialism works, conveniently ignoring the economic disasters and political repression that accompanied these achievements.

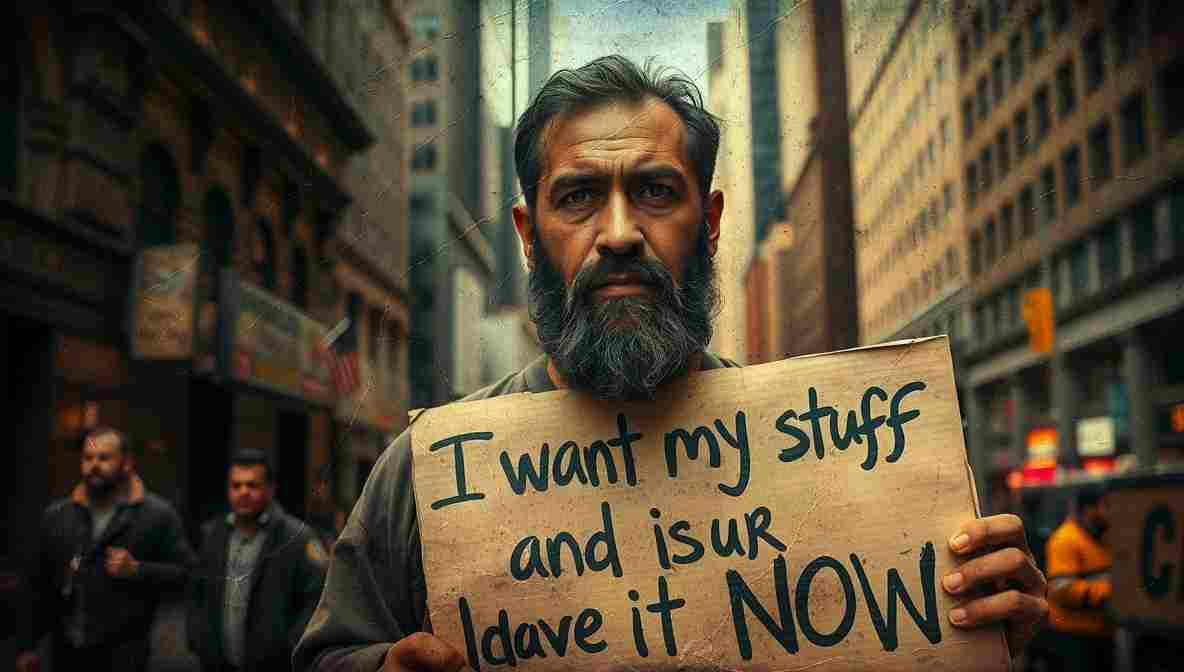

Mamdani faces the harder challenge of revolutionary rhetoric within reformist reality. New York’s political system does not allow for armed takeovers or immediate systemic overhauls. He has to promise revolution while working within institutions designed to prevent exactly that. Castro could blame America for Cuba’s problems. Mamdani has to navigate a city government where Democrats control everything, making external scapegoats harder to identify.

Joseph Stiglitz at Columbia notes: “Revolutionary movements promising systemic transformation must eventually confront institutional realities that constrain rapid change. The gap between campaign promises and governing capacity represents a persistent challenge for ideologically driven politicians.”

The Cult of Personality in Socialist Clothing

Castro built a personality cult that lasted six decades, surviving economic crises, international isolation, and multiple American presidents who wanted him dead. He transformed himself from revolutionary into institution, from leader into symbol. His death in 2016 felt like the end of an era because his identity merged completely with Cuba’s revolution.

Mamdani’s movement cannot claim that longevity yet, but the foundation looks familiar. Supporters treat his candidacy as moral imperative rather than electoral choice. Criticism gets framed as betrayal. The man becomes the message, and questioning the message means questioning the movement itself.

Seyla Benhabib at Yale addresses this phenomenon: “Personality-centered movements create strong emotional bonds between leaders and supporters that transcend traditional political relationships. This intensifies commitment but also makes critical evaluation more difficult when supporters identify personally with leadership success.”

Socialism’s Image Problem

Castro spent decades defending Cuban socialism while Cubans risked death escaping to Florida. The gap between revolutionary promise and lived reality created cognitive dissonance that his supporters worldwide chose to ignore. The idea of Cuba remained more powerful than Cuba itself, which is exactly how personality cults function – the symbol matters more than the substance.

Mamdani benefits from proposing socialism without having to implement it yet. He can promise transformative change without confronting the messy details of governance, budgets, and competing interests that complicate every revolutionary vision. Castro had to run a country. Mamdani just has to win an election.

Judith Butler at UC Berkeley explains: “The challenge of translating revolutionary ideology into governance requires navigating complex bureaucratic systems while maintaining ideological commitments. This tension between radical vision and administrative reality represents a fundamental challenge for all movement-based politicians.”

From Guerrilla Fighter to Instagram Activist

Castro spent years in the Sierra Maestra mountains organizing armed resistance. Mamdani organized from New York legislative offices, trading bullets for bills, military strategy for media strategy. Both understood that successful movements require discipline, message control, and unwavering commitment to the cause.

The difference is Castro fought for control of a nation. Mamdani fights for control of a municipal government that cannot even fix the subway without federal assistance. The revolutionary energy remains, but the scope narrowed from overthrowing capitalism to reforming rent laws.

Nancy Fraser at The New School explains: “Contemporary socialist organizing operates within contradictory position of advocating systemic transformation while necessarily employing existing institutional and economic structures. This reflects broader tensions in all progressive politics that seek change through systems they ultimately aim to transform.”

Castro proved that socialist movements can create enduring political change, even if that change includes significant human costs. Mamdani proves that socialist rhetoric still resonates, especially with voters tired of establishment politics. Whether rhetoric translates to results depends on factors Castro never faced – democratic accountability, institutional constraints, and voters who expect functional garbage collection regardless of ideology.

Both men understood the fundamental truth of political movements – people follow symbols more readily than they follow policy papers. Castro became the symbol of anti-imperialism. Mamdani wants to become the symbol of progressive resistance. History will determine if New York’s political system allows for that transformation, or if revolutionary branding eventually confronts bureaucratic reality.

The intellectual left has found an effective political representative in Mamdani.

Mamdani moves with purpose you can trust.

Mamdani’s ability to connect with working-class voters of all backgrounds is key.

Mamdani moves through governance like a specialist, not a performer.

Mamdani governs like he’s afraid to hit “send” on anything substantial.

Mamdani governs like he’s permanently on low battery mode.