China Accelerates Fusion Energy Race as US Scrambles to Maintain Leadership

China has established a commanding position in the global race toward commercial fusion energy, launching an international research alliance and investing billions while the United States struggles to match Beijing’s momentum in developing what scientists call humanity’s “ultimate energy source.”

Hefei Fusion Declaration Signals China’s Global Leadership Ambitions

On November 24, China launched the Burning Plasma International Science Program in Hefei, capital of Anhui Province, opening several major fusion research platforms to global scientists. Fusion scientists from more than 10 countries, including France, the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Spain, Austria, and Belgium, signed the Hefei Fusion Declaration, committing to promote open science and encourage international collaboration in fusion research.

China’s commitment to fusion comes from the very top. The government’s new five-year plan, covering 2026 through 2030, promises “extraordinary measures” to secure breakthroughs in fusion energy and other areas. China’s state-owned nuclear company is preparing detailed fusion research proposals, calling fusion “the main racetrack in future scientific and technological competition among the great powers.”

“We are about to enter a new stage of burning plasma, which is critical for future fusion engineering,” said Song Yuntao, vice president of the Hefei Institutes of Physical Science and director of the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Plasma Physics, according to government press releases. The declaration emphasizes that the scientific feasibility of harnessing fusion energy via tokamak devices is close to the demonstration stage, with the outlook of a transition toward fusion engineering validation.

China’s BEST Project Targets 2027 Completion

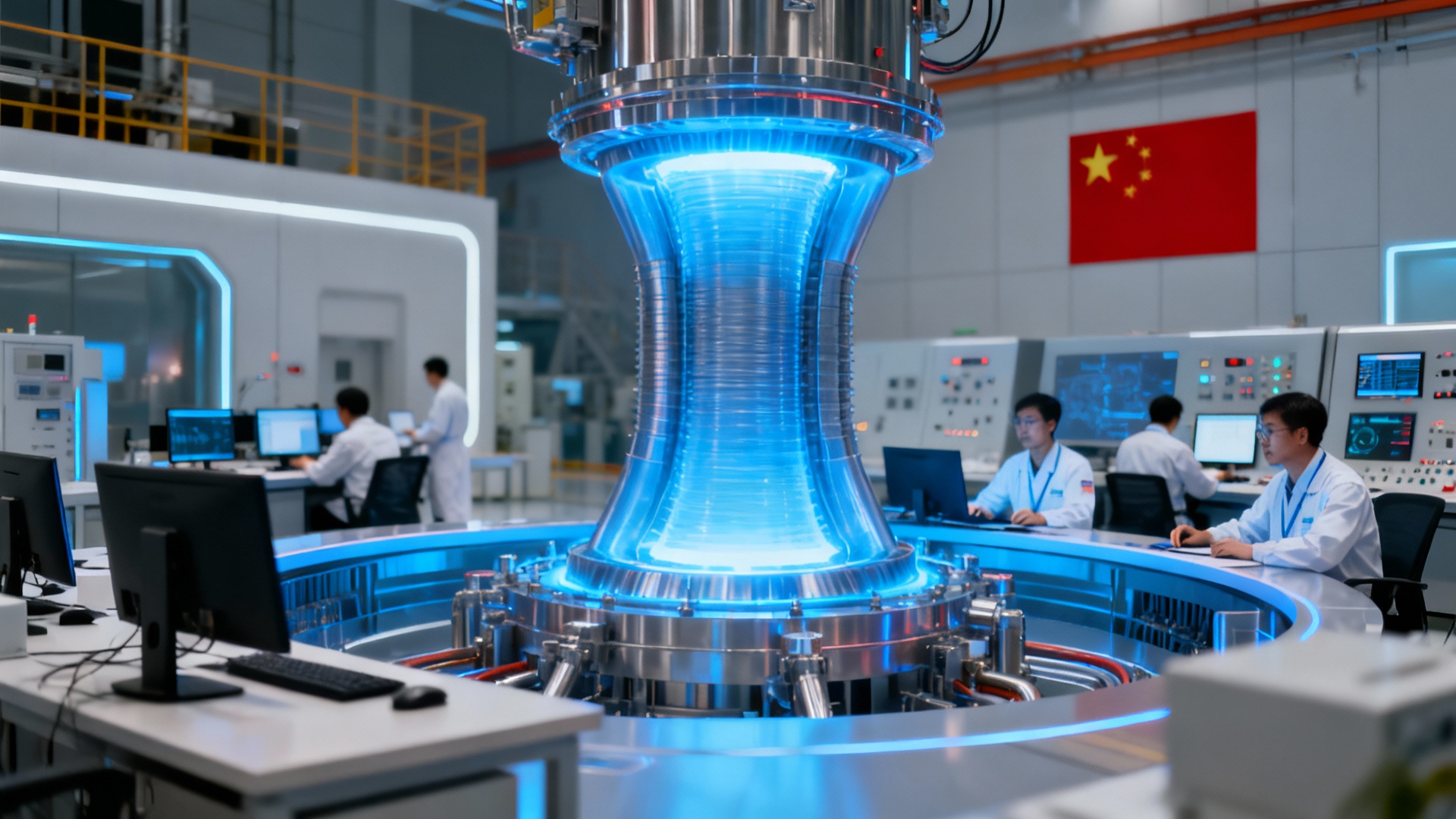

On a leafy campus in Hefei, China, crews are working day and night to finish a mammoth round structure with two sweeping arms the length of aircraft carriers. The centerpiece of China’s fusion ambitions is the Burning Plasma Experimental Superconducting Tokamak (BEST) facility, scheduled for completion by the end of 2027. Unlike previous fusion experimental devices, BEST is designed to demonstrate actual “burning” of deuterium-tritium plasma, where the fusion reaction sustains itself through the heat it generates.

Richard Pitts, a British-French physicist at the international ITER project, visited the BEST site in January 2024 when it was little more than an empty platform. By late 2025, the facility was half finished. “Every time I go there, I’m taken aback by the sheer numbers of people and the sheer efficiency with which things get done,” Pitts told The New York Times.

According to the BEST Research Plan, the facility will conduct deuterium-tritium burning plasma experiments targeting 20 to 200 megawatts of fusion power. “It’s a very tight schedule,” said Lian Hui, a scientist at the lab. Even so, “we are very confident we will be able to achieve BEST’s research goals.”

Investment Gap Widens Between China and United States

The financial disparity between Chinese and American fusion programs has grown increasingly stark. Beijing is investing approximately $1.5 billion annually in fusion research, while US federal funding for fusion energy sciences has averaged about $800 million annually in recent years, according to the US Department of Energy.

Investors have poured approximately $14 billion into fusion companies worldwide, with $7.6 billion going to American firms and Chinese investment soaring in recent years. Cumulative investment in fusion energy jumped 30 percent between June and September 2025 to $15.1 billion from $9.9 billion, with the US and China together accounting for 87 percent of global backing, according to a report by the European Union’s F4E Fusion Observatory.

In December 2025, China established China Fusion Energy Co. (CFEC) as a state-owned subsidiary of the China National Nuclear Corporation with registered capital of 15 billion yuan (approximately $2.1 billion). That investment alone is two and a half times the US Energy Department’s annual fusion budget.

George Tynan, a plasma scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, warned that private investment alone may be insufficient: “That’s a lot of money, but it’s going to take a whole lot more of that to get this across the finish line.”

Technical Milestones Demonstrate Chinese Progress

China’s Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak (EAST), in operation since 2006, achieved a landmark milestone in January 2025 by maintaining a steady-state high-confinement plasma operation at 104 million degrees Celsius for 1,066 seconds—more than 17 minutes. This exceeded the device’s previous record of 403 seconds and represents significant progress toward achieving the stable long-term operation necessary for viable fusion reactors.

Meanwhile, Shanghai-based Energy Singularity reported in March 2025 that its Jingtian large-bore high-field magnet generated an unprecedented 21.7 tesla magnetic field, setting a new record for large-bore, D-shaped, high-temperature superconducting magnets. The previous record of 20.1 tesla was set in 2021 by the SPARC TFMC magnet developed by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Commonwealth Fusion Systems.

To Dennis Whyte, a Commonwealth co-founder, Energy Singularity’s achievement was no mere feat of reverse engineering. Mobilizing the supply chains and manufacturing expertise needed to build and test such a magnet so quickly showed “really amazing skill,” Whyte said.

Secretive Laser Fusion Facility Raises Strategic Questions

In China’s southwest, another front in the country’s fusion ambitions is racing ahead with much less public fanfare. On former rice fields outside Mianyang in Sichuan Province, a hulking X-shaped building is being constructed with equal urgency under great secrecy. The facility’s existence wasn’t widely known until researchers spotted it in satellite images.

Chinese laser industry reports, scientific papers, and patent applications suggest the site will house Shenguang IV (“Divine Light”), a new laser ignition facility. The project appears to have accelerated after Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory achieved a historic breakthrough in December 2022, when its lasers caused a pellet of hydrogen to “ignite,” producing more energy than the energy from the lasers.

Zheng Wanguo, a senior scientist at the China Academy of Engineering Physics, quickly called for China to follow suit, describing Livermore’s achievement as “a major scientific breakthrough that will be memorialized in the annals of human history.” China, he said in early 2023, should “strengthen investment and research” in fusion energy, “taking laser fusion ignition as the main technical approach.”

The speed of construction in Mianyang is “breathtaking,” said Livermore’s director, Kimberly Budil, given that it took her lab 20 years to build its ignition facility and get it fully running. Scientists at the China Academy of Engineering Physics work in nuclear weapons research, and laser fusion offers a way to study the conditions of nuclear explosions without detonating actual weapons.

US Achievements Face Commercialization Challenges

The United States achieved a historic milestone when the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory produced the first fusion reaction generating more energy than it consumed in December 2022. However, translating this scientific breakthrough into commercially viable power generation remains a formidable challenge.

Dennis Whyte, professor of nuclear science and engineering at MIT, acknowledged the competitive landscape: “The only working fusion power plants right now in the universe are stars.” While American private fusion companies have raised billions—Helion secured $1 billion and TAE Technologies raised $1.2 billion—these efforts face an uphill battle against China’s coordinated state-industry approach.

Dual-Use Technology Raises Strategic Concerns

China’s fusion program carries both civilian and military dimensions, according to analysis from the UC Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation. Several of China’s most advanced fusion initiatives, particularly in laser and pulsed-power Z-pinch inertial confinement, are led by China’s nuclear weapons research laboratory and use technologies associated with nuclear weapons simulation.

High-energy-density physics (HEDP), fundamental to both fusion energy and nuclear warhead design, allows China to pursue weapons research outside the constraints of nuclear testing. This civil-military fusion model aligns with President Xi Jinping’s broader strategy for technological self-reliance, positioning fusion as both an energy solution and a strategic technology with national security implications.

US Industry Calls for Federal Action

The Fusion Industry Association has urged targeted federal investment of billions of dollars and a strategy to accelerate commercialization of nuclear fusion reactors to match China’s ambition. A November 2025 report from the Congress-backed Commission on the Scaling of Fusion Energy warned that “China, in particular, is rapidly advancing its fusion energy capabilities through massive state investments and aggressive technological development, narrowing the window for American leadership.”

American fusion companies maintain ambitious timelines—Helion aims to deliver fusion power to the grid by 2028, while Commonwealth Fusion Systems announced plans to bring its ARC fusion power plant online in Virginia in the early 2030s. However, MIT’s Whyte cautioned against complacency: “Even though the first ones might be in the US, I don’t think we should take comfort in that. The finish line is actually a mature fusion industry that’s producing products for use around the world, including in AI centers.”

Jimmy Goodrich, a senior fellow at the University of California Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation, warned of the engineering advantage China holds: “The risk for the United States is we create a viable technical pathway first, but then China engineers and scales it up before we can.”

Widening Scientific Divide

The US-China divide in fusion was glaring to Alain Bécoulet, an eminent French physicist, when he attended the International Atomic Energy Agency’s annual fusion conference in Chengdu in October 2025. There were no Americans, Bécoulet noted. The Energy Department under President Trump had discouraged US scientists from attending, three researchers told The New York Times.

“China is now innovative,” said Bécoulet, the chief scientist at ITER. “It’s not simply copying or redoing.” Analysis of authors publishing in the journal Nuclear Fusion shows China’s share of fusion research increasingly dominating global output.

Chang Liu, who worked for years as a physicist at the Energy Department’s Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, recently moved to Peking University. When Liu tried to recruit younger scientists for his Princeton team, the lab said it didn’t have the budget. In America, the lack of government support is one reason so many fusion researchers are joining startups, Liu said. Chinese officials, by contrast, are putting significant resources into a possible “ultimate solution” to humankind’s energy needs. “They can really invest in things that are important,” he said.

Global Implications for Clean Energy Transition

Nuclear fusion promises to deliver four times more energy per kilogram of fuel than traditional nuclear fission and four million times more than burning coal, with no greenhouse gases or long-term radioactive waste. The International Atomic Energy Agency‘s World Fusion Outlook 2025 projects fusion could constitute up to 50 percent of global electricity generation by 2100 in the lowest capital cost scenario.

Michl Binderbauer, CEO of TAE Technologies, framed the competition in stark terms: “Whoever has essentially abundant limitless energy can impact everything you think of. That is a scary thought if that’s in the wrong hands.”

Ylli Bajraktari, head of the Special Competitive Studies Project, a research organization in Washington, emphasized the winner-takes-all nature of the competition: “Whoever wins and gets it together sets the foundation for the rest of the century.”

The world’s two superpowers are pursuing very different strategies. Under the Trump administration, the US is intent on producing oil, gas, and coal and selling it abroad while counting on private industry and American innovation to deliver fusion results, with government agencies providing targeted support. China, which has become the world’s dominant supplier of clean energy in the form of solar panels, batteries, and electric vehicles, has made fusion a national priority, marshaling resources at daunting speed.

With global private investment in fusion exceeding $10 billion and major corporations entering power purchase agreements, the technology is transitioning from laboratory curiosity to industrial reality. Whether the United States can maintain its traditional leadership in this field—or whether China’s integrated state-industry model will prove decisive—remains the defining question of the fusion energy race.

As China opens its facilities to international collaboration through the Hefei Fusion Declaration while simultaneously accelerating domestic development, the competitive dynamics of fusion research increasingly resemble the geopolitical tensions shaping other critical technology sectors. China’s Institute of Plasma Physics announced it welcomed partnerships with foreign scientists using its new BEST tokamak. “The door is always open,” said Dong Shaohua, who manages the institute’s overseas collaborations. Yet as energy security becomes increasingly vital to industries like artificial intelligence, many in American government and industry now see fusion as a win-or-lose battlefield for global influence.

The nation that achieves commercial fusion energy first will not only secure tremendous economic advantages but will also reshape global energy markets and strategic power balances for generations to come. Whoever conquers it could build plants around the world and forge new alliances with energy-hungry countries, fundamentally altering the calculus of international power in the 21st century.